DISCLAIMER: Foreign Exchange trading is a high-risk activity. This post or any content on this blog should not be taken as financial or trading advice of any kind.

A very popular trading indicator is called Average True Range, or simply ATR. This is an indicator to measure market volatility in terms of the difference between the highest and lowest prices of a day, session or any period of time, being a useful tool for traders that are trying to predict how much the price of a given asset will move on the current or future period.

Its value comes from the taking the average of the true range, the latter being calculated as the maximum of: high - low; abs(high - previous close); abs(low - previous close). The equation looks like this:

\[TR = max[(High - Low),abs(High - PrevClose),abs(Low - PrevClose)]\] \[ATR(n) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^nTR_i}{n}\]The reason why the indicator doesn’t use only High and Low is that sometimes price will gap from one session to the next. This is particularly frequent with markets that have limited session times, like stocks and futures. With Forex, the target of this article, the market is open most of the time between monday to friday, and usually gaps will happen, if they happen at all, on the monday opening (sunday evening for most countries). We will keep the equation like that because most softwares do it like that.

ATR as a range predictor

As stated before, a common usage of the ATR is to predict future range. This is useful to set take-profits and stop-losses. If, on average, price has a range of 100 pips (or 1000 points) during a single day, a trader can calculate, from its entry point, how much space is there for a probable move in his or hers direction, and set the target with this difference in mind. Or maybe the trader can expect a reversal whenever the current range has already reached the ATR value.

Trading is an activity of dealing with probabilities, and every percentual point can make a big difference in the long term outcome of a strategy.

Whenever we talk about an average, we somehow have a normal distribution in mind. Even if someone has no clue what a normal distribution is, it is easy to assume that if you are dealing with an average, that is probably the value with a 50% chance of happening.

Of course this doesn’t happen in real life (or “real” statistics, should I say). There are various probability distributions and there are plenty that don’t have a nice looking, symmetrical aspect.

One big issue with this indicator is that it is averaging values that don’t have a clear upper limit but have a fixed lower limit. While any news event or market activity can cause the market to move, and therefore, produce a positive price range, there is no circumstance where we can have a negative range.

The pip (or point) range for any particular timeframe, could be expressed as:

\[Range \in \mathbb{R}, Range \geq 0\]This means that this variable can only have outliers on the upper side; while we will never have a range of -200 points (because the formula doesn’t allow it), we can have ranges of +200, +1000, +200000 or more pips (there might be a limit that would mean the colapse of the entire world economy, but let’s not get into that).

My goal here, then, is to check how well does the ATR predicts the next session range, given that this is a common way of using the tool. The hypothesis is that this indicator gives a biased result, and that the next sessions’ range is at least equal the ATR less than 50% of the observations.

A first test with one pair and one timeframe

I will start by analyzing only the British Pound/US Dollar (GBPUSD) pair with the daily timeframe (1440 minutes). This will allow me to create the necessary code and have a first result, to later expand to more pairs and timeframes.

# Imports and read file

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

gbpusd = pd.read_csv('/content/drive/My Drive/Colab Notebooks/ATR study/GBPUSD1440.csv')

# Clean data

gbpusd.columns = ['Date','Time','Open','High','Low','Close','Volume']

gbpusd = gbpusd.drop(['Time','Volume'], axis=1)

gbpusd['Date'] = pd.to_datetime(gbpusd['Date'])

# Calculate ranges

# I usually do everything separated so there are not too many chained methods

gbpusd['Range'] = gbpusd['High'] - gbpusd['Low']

gbpusd['TRangeH'] = abs(gbpusd['High'] - gbpusd['Close'].shift(1))

gbpusd['TRangeL'] = abs(gbpusd['Low'] - gbpusd['Close'].shift(1))

gbpusd['TR'] = gbpusd[['Range','TRangeH','TRangeL']].max(axis=1)

# Calculate ATR for 14 trading days

gbpusd['ATR14'] = gbpusd['TR'].rolling(window=14).mean()

# Create a column to check if the range of a given session hit the ATR or not

# Have to remember to always calculate the TR against the ATR from the previous period

gbpusd['HitATR'] = gbpusd['TR'] > gbpusd['ATR14'].shift(1)

# Calculate the ratio of observations where the range hit the ATR

# I start from the 15th row because we needed a window of 14 periods to calculate the ATR

print(gbpusd.iloc[14:,]['HitATR'].sum()/gbpusd.iloc[14:,]['HitATR'].count())

0.4191897654584222

This first result shows that the range for any given day reached the ATR(14) value of the previous day only 41.9% of the time. Let’s plot all the observations in a chart to see how this data looks like.

# I will create another column to calculate, in %, how far away the current range was in terms of the ATR

gbpusd['Diff'] = (gbpusd['TR'] - gbpusd['ATR14'].shift(1))/gbpusd['ATR14'].shift(1) * 100

gbpusd.iloc[14:,].head(5)

Date Open High Low Close Range TRangeH TRangeL TR ATR14 HitATR Diff

14 1993-04-16 1.5370 1.5425 1.5220 1.5250 0.0205 0.0050 0.0155 0.0205 0.018379 True 10.469592

15 1993-04-19 1.5270 1.5435 1.5250 1.5422 0.0185 0.0185 0.0000 0.0185 0.019057 True 0.660707

16 1993-04-20 1.5410 1.5560 1.5375 1.5480 0.0185 0.0138 0.0047 0.0185 0.019679 False -2.923538

17 1993-04-21 1.5475 1.5535 1.5350 1.5400 0.0185 0.0055 0.0130 0.0185 0.019143 False -5.989111

18 1993-04-22 1.5390 1.5645 1.5330 1.5620 0.0315 0.0245 0.0070 0.0315 0.019500 True 64.552239

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8))

sns.set_color_codes()

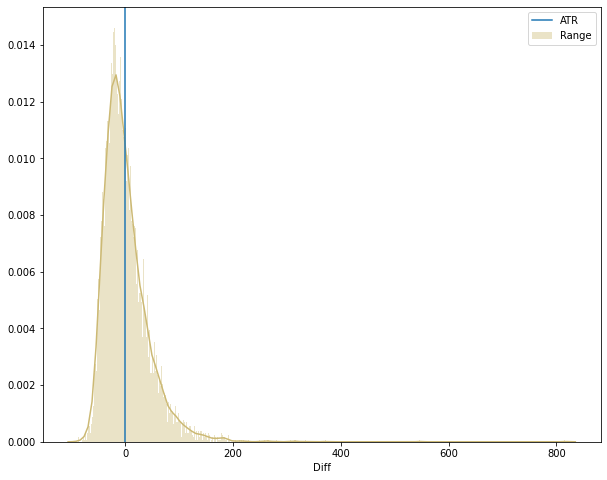

sns.distplot(gbpusd['Diff'], kde=True, rug=False, bins=500, color="y", label='Range');

plt.axvline(0, 0, 1, label='ATR')

plt.legend()

gbpusd['Diff'].describe()

count 7035.000000

mean 1.390805

std 42.930905

min -87.987520

25% -26.445736

50% -7.448790

75% 19.560309

max 816.574020

Name: Diff, dtype: float64

This plot and the describe method shows some outliers. Of course, there are days where some big event will make the price range go really high. We can have an idea if they are a recurrent event, taking a look on how many observations we have with a range 200% higher than the ATR.

print('Total observations with range 200% or more above ATR: ' + str(gbpusd['Diff'][gbpusd['Diff'] > 200].count()))

print('Rate of observations with range 200% or more above ATR: ' + str(round(100*(gbpusd['Diff'][gbpusd['Diff'] > 200].count())/gbpusd['Diff'].count(),3)) + '%')

Total observations with range 200% or more above ATR: 17

Rate of observations with range 200% or more above ATR: 0.242%

With these outliers corresponding to only 0.242% of the dataset, it is better to perform the analysis without them and redraw the chart.

(Keep in mind that days with extremely high volatility usually come with high spreads and unusual market behavior).

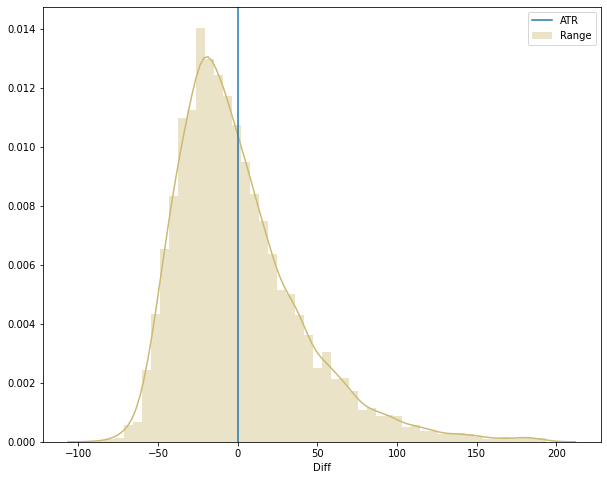

x = gbpusd[gbpusd['Diff'] <= 200]

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8))

sns.distplot(x['Diff'], kde=True, rug=False, bins=50, color="y", label='Range');

plt.axvline(0, 0, 1, label='ATR')

plt.legend()

With a better looking image we can see that the data is more heavily distributed on the left side of the blue line, indicating that more often than not the price range does not hit the ATR. To be sure, we can calculate the median and plot it on the chart (the median represents the value that separates the density curve in two halves, or 50%).

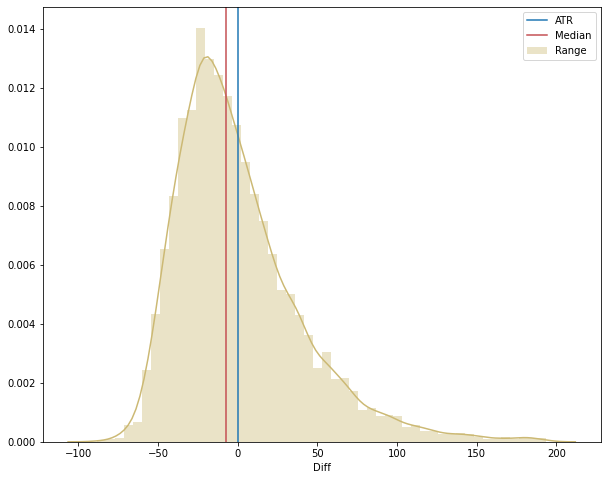

median = gbpusd['Diff'].median()

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8))

sns.distplot(x['Diff'], kde=True, rug=False, bins=50, color="y", label='Range');

plt.axvline(0, 0, 1, label='ATR')

plt.axvline(median, 0, 1, color='r', label='Median')

plt.legend()

In the end, we could have just plotted the median against the ATR and we would know that the ATR is hit less than 50% of the time. However, it is important to construct the idea in a organized way because it can give some interesting ideas going ahead, for example:

- Checking different pairs in different timeframes can yield different results;

- Trying another parameter for the ATR indicator can serve as a better prediction;

- We could use the median, instead of the mean, or even the mode as the indicador (they would come with their own peculiarities though).

Testing with a bigger sample

Now that we have this data for the GBPUSD pair from april-1993 until may-2020, we can check if this behavior happens with other pairs and different ATR periods.

I downloaded daily charts from 28 pairs. With each dataset we will run the calculations for every ATR parameter from 1 to 100. We will get the rate of times the ATR was hit for all combinations. After that we can plot the data and draw our final conclusions.

Using an ATR of 1 period means that we are taking the average of a single day, which is the same as the range of that day without calculations.

I uploaded the csv files into Google Drive (I used Colab for this code). To read the files I will use Dask because it can read more than one csv’s at the same time, but then I turn back to Pandas because we can then use the unique() method, which is not yet implemented in Dask.

import dask.dataframe as dd

dataset = dd.read_csv('/content/drive/My Drive/Colab Notebooks/ATR study/*.csv', include_path_column=True, names=['Date', 'Time', 'Open', 'High', 'Low', 'Close', 'Volume'])

# It is important to use include_path_column, otherwise we won't be able to know which row relates to each pair

# We just have to clean this last column to get only the pair name and not the entire file path

dataset.head(2)

Date Time Open High Low Close Volume path

2003.01.21 10:00 0.9072 0.9087 0.8967 0.9025 194 /content/drive/My Drive/Colab Notebooks/ATR st...

2003.01.21 13:00 0.9072 0.9087 0.8967 0.9025 194 /content/drive/My Drive/Colab Notebooks/ATR st...

# I chained two replace methods, which might not look so nice but is quite efficient on doing the job

dataset['path'] = dataset['path'].str.replace('/content/drive/My Drive/Colab Notebooks/ATR study/','').str.replace('1440.csv','')

dataset = dataset.rename(columns={'path': 'Pair'})

dataset.head(2)

Date Time Open High Low Close Volume Pair

2003.01.21 10:00 0.9072 0.9087 0.8967 0.9025 194 AUDCAD

2003.01.21 13:00 0.9072 0.9087 0.8967 0.9025 194 AUDCAD

# Clean data

dataset = dataset.drop(['Time','Volume'], axis=1)

dataset['Date'] = dd.to_datetime(dataset['Date'])

# Transform Dask dataframe into Pandas dataframe with compute

df = dataset.compute()

# Create list to iterate on

pairs_list = df['Pair'].unique()

# Create list of ATR parameters

atr_list = range(1, 101)

# Create dataframe to gather statistics

df_stats = pd.DataFrame()

for pair in pairs_list:

df_calc = df[df['Pair'] == pair]

# Calculate ranges

df_calc['Range'] = df_calc['High'] - df_calc['Low']

df_calc['TRangeH'] = abs(df_calc['High'] - df_calc['Close'].shift(1))

df_calc['TRangeL'] = abs(df_calc['Low'] - df_calc['Close'].shift(1))

df_calc['TR'] = df_calc[['Range','TRangeH','TRangeL']].max(axis=1)

# Inside this loop, we will iterate on the ATR parameter values to get all the calculations done

for param in atr_list:

# Calculate ATR

df_calc['ATR'] = df_calc['TR'].rolling(window=param).mean().copy()

# Create a column to check if the range of a given session hit the ATR or not

df_calc['HitATR'] = df_calc['TR'] > df_calc['ATR'].shift(1).copy()

# Calculate the ratio of observations where the range hit the ATR

ratio_hit = df_calc.iloc[param:,]['HitATR'].sum()/df_calc.iloc[param:,]['HitATR'].count()

# Calculate, in %, how far away the current range was in terms of the ATR

df_calc['Diff'] = ((df_calc['TR'] - df_calc['ATR'].shift(1))/df_calc['ATR'].shift(1) * 100).copy()

# Calculate the median of the difference

median = df_calc['Diff'].median()

# Calculate the mean of the difference

mean = df_calc['Diff'].mean()

# Insert stats into dataframe

stats_list = [[pair, param, ratio_hit, median, mean]]

df_stats = df_stats.append(stats_list)

df_stats.columns = ['Pair', 'ATR period', 'Hit Ratio', 'Median', 'Mean']

df_stats.head(5)

Pair ATR period Hit Ratio Median Mean

AUDCAD 1 0.492657 -0.642590 10.796573

AUDCAD 2 0.466503 -3.601108 5.965425

AUDCAD 3 0.446126 -4.936540 4.217882

AUDCAD 4 0.437764 -5.314010 3.153328

AUDCAD 5 0.438530 -5.309735 2.633682

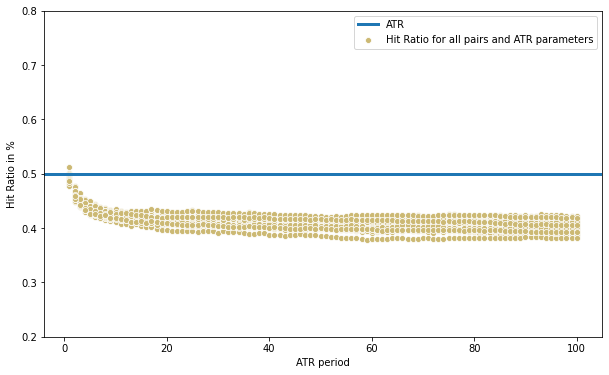

Now we can finally make some plots in order to better visualize the data.

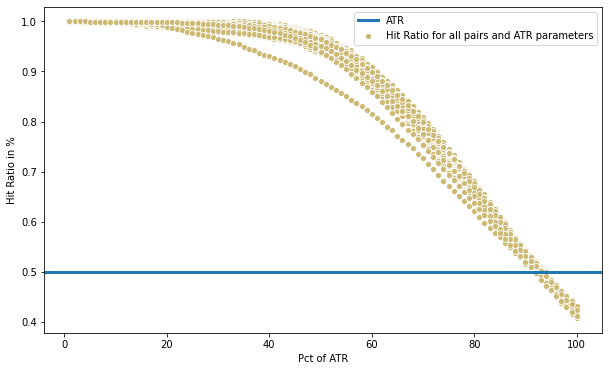

plt.figure(figsize=(10,6))

sns.scatterplot(x=df_stats['ATR period'], y=df_stats['Hit Ratio'], color="y", label='Hit Ratio for all pairs and ATR parameters');

plt.axhline(0.5, 0, 1, label='ATR', linewidth=3)

plt.ylabel('Hit Ratio in %')

plt.ylim(0.2, 0.8)

plt.legend()

print(df_stats[df_stats['Hit Ratio'] >= 0.5][['Pair','ATR period','Hit Ratio']])

Pair ATR period Hit Ratio

CADCHF 1 0.500411

GBPCAD 1 0.511964

Interestingly we have two cases where the ATR was hit at least 50% of the time: both cases using an ATR of 1 period (so there is no average taken, just the value of the previous day’s range), and just barely above 50%.

We can also notice that the scatter plot shows a clear correlation between ATR period and the hit ratio. With very low parameter values the ATR serves better as a prediction for the next day’s range than with higher values. A parameter of around 15 to 100 produces little difference.

We can conclude that the average of the most recent days are more relevant to predict future range. That said, it is still not the best prediction, with most cases falling short of 50% and a curious aspect shown below:

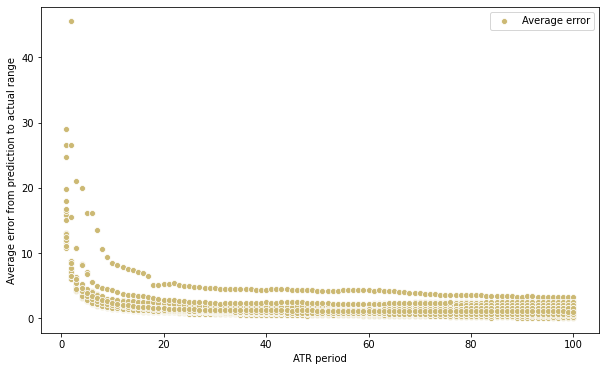

plt.figure(figsize=(10,6))

sns.scatterplot(x=df_stats['ATR period'], y=df_stats['Mean'], color="y", label='Average error')

plt.ylabel('Average error from prediction to actual range')

plt.legend()

Here we can see that the average error increases dramatically when the ATR parameter is small. This suggests that, even though on the long term a lower parameter will serve as a correct prediction more often, when it misses, it misses by a higher margin. This behavior can also be expected because a low sample is more prone to produce unreliable indicator estimations.

Analyzing a possible adjustment for the ATR

One alternative could be to simply take a percentage of the ATR value for the prediction. This will naturally cause the hit ratio to increase, but will come at the cost of getting a lower expected range. Let’s take, for example, the same ATR parameter we used in the first example, 14 periods.

# Create dataframe to gather statistics

df_stats_alt = pd.DataFrame()

pct_atr = range(1,101)

for pair in pairs_list:

df_calc = df[df['Pair'] == pair]

# Calculate ranges

df_calc['Range'] = df_calc['High'] - df_calc['Low']

df_calc['TRangeH'] = abs(df_calc['High'] - df_calc['Close'].shift(1))

df_calc['TRangeL'] = abs(df_calc['Low'] - df_calc['Close'].shift(1))

df_calc['TR'] = df_calc[['Range','TRangeH','TRangeL']].max(axis=1)

# Inside this loop, we will use the ATR 14 to get the hit ratio results

for paramt in pct_atr:

# Calculate ATR

df_calc['ATR'] = df_calc['TR'].rolling(window=14).mean()

# Create a column to check if the range of a given session hit the ATR or not

df_calc['HitATR'] = df_calc['TR'] > (df_calc['ATR'].shift(1) * paramt/100)

# Calculate the ratio of observations where the range hit the ATR

ratio_hit = df_calc.iloc[14:,]['HitATR'].sum()/df_calc.iloc[14:,]['HitATR'].count()

# Insert stats into dataframe

stats_list_alt = [[pair, paramt, ratio_hit]]

df_stats_alt = df_stats_alt.append(stats_list_alt)

df_stats_alt.columns = ['Pair', 'Pct of ATR', 'Hit Ratio']

plt.figure(figsize=(10,6))

sns.scatterplot(x=df_stats_alt['Pct of ATR'], y=df_stats_alt['Hit Ratio'], color="y", label='Hit Ratio for all pairs and ATR parameters');

plt.axhline(0.5, 0, 1, label='ATR', linewidth=3)

plt.ylabel('Hit Ratio in %')

plt.legend()

Here we see, for example, that if we use 40% of the ATR, we predict the range to be at least that value more than 90% of the time. Having a 90% certainty of anything is a big deal, but if it is only with 40% of the average range, than it becomes not so meaningful.

If we use 60% of the ATR, we get more than 80% of “good enough” predictions. More than 60% of the ATR and we see a sharp decrease in accuracy.

Conclusion

The ATR, as much as it is a good indicator for providing an insight about the volatility of a market, has to be used cautiously when a trader is trying to predict future range.

Still, it is one of the better tools available, very easy to calculate and with a variety of uses. And, of course, if we are using the ATR to get a value for our stop losses, than we might even benefit from the fact that the predicted value is reached less than 50% of time.

In future posts we will discuss other methods and different approaches do the ATR, specially with intraday data.